Captain Jonathan, Gentleman

The following story is about Jonathan Danforth, my 8th great paternal grandfather. Jonathan was born on February 28, 1627 in Framlingham, England and died at the age of 85 on September 7, 1712 in Billerica, Massachusetts. By all historical accounts, he was a respected community leader and a gifted surveyor. In the inventory of his estate, he is referred to as “Captain Jonathan, Gentleman.”

Part two touches on Jonathan’s involvement and response to conflicts between Native Americans and colonists. Part three provides a brief story about Jonathan’s brother, Thomas Danforth, who played a role in the Salem witch trials.

Part One – Early New England Colonist, Gifted Surveyor, Community Leader

When

Jonathan was five years old, he came to America with his father,

Nicholas Danforth, brothers Thomas and Samuel and his three sisters,

Anna, Lydia, and Elizabeth. Jonathan’s mother had died a week before he

was a year old.

The Danforth family sailed on the Griffin, departing England on August 1,1634 arriving in Boston on September 18. The Griffin weighed 300 tons and carried about one hundred passengers and cattle for the colonies plantations. It is believed that he spent his youth in New-Towne (later Cambridge) living with his father until his death in 1638 and then lived with an elder, married sister. At the age of twenty, he left Cambridge and was a founding father of Billerica, Massachusetts. He married Elizabeth Poulter in Boston on November 22, 1654 and together they had eleven children. Elizabeth died on October 7, 1689. Their daughter, Sarah (1676-1747), married William French (my 7th great-grandfather).

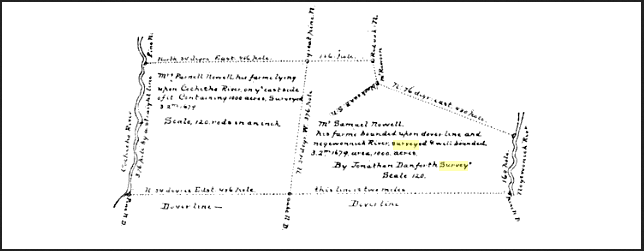

Jonathan was a noted land surveyor and his descriptions of this service fill some 200 pages in the first volume of Land Grants. He held many public offices: deputy for the town, town clerk, selectman and he also represented the town at the General Court in 1684/5.

“He rode the circuit, chain’d great towns and farm, To good behavior, and by well marked stations, He fixed their bounds for many generations. His art ne’er failed him, though the loadstone faile. When oft by mines and streams it was assailed. All this is charming, but there’s something higher. Gave him the lustre which we most admire.” Poem by his nephew, the Rev. John Danforth of Dorchester.

Part Two – King Philip’s War and the Fate of Indian Children

It

was also an especially bloody war—the bloodiest, in terms of the

percentage of the population killed, in American history. The figures

are inexact, but out of a total New England population of 80,000,

counting both Indians and English colonists, some 9,000 were killed—more

than 10 percent. Two-thirds of the dead were Indians, many of whom died

of starvation. Indians attacked 52 of New England’s 90 towns, pillaging

25 of those and burning 17 to the ground. The English sold thousands of

captured Indians into slavery in the West Indies. New England’s tribes

would never fully recover. Blood and Betrayal: King Philip’s War

Starting

in 1646, colonists began to establish “praying towns” in an effort to

convert New England tribes to Christianity. By the year 1675, there

were an estimated 1,100 Praying Indians in Massachusetts located in fourteen Praying Towns.

These towns were situated so as to serve as an outlying wall of defense

for the colony. Wamesit, a praying town, was located within five miles

of Billerica.

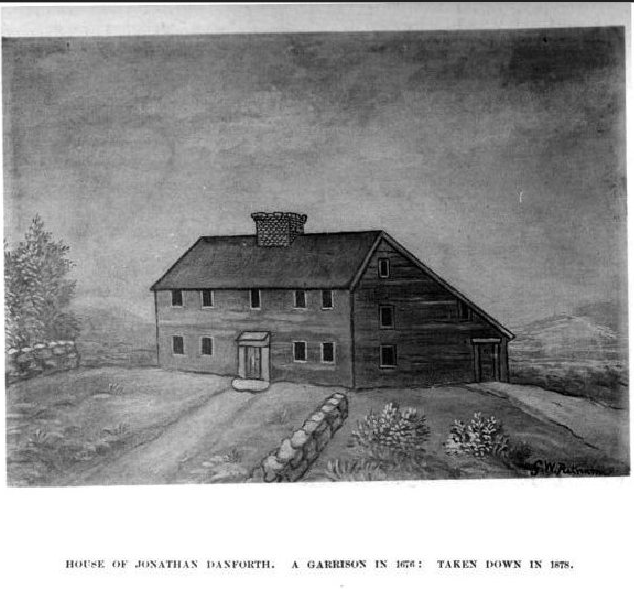

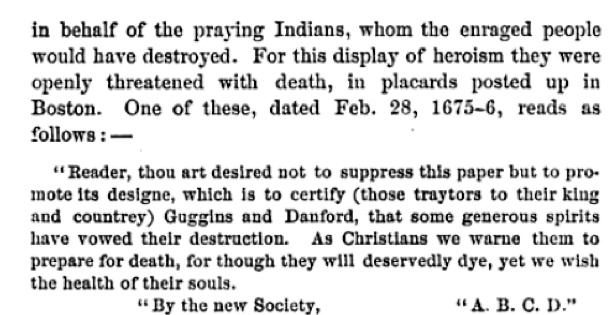

Jonathan Danforth served during King Philip’s War under Major Daniel Gookin. The town of Billerica had twelve garrison houses, each was providing a defensive space for four to seven families. The homes of Jonathan Danforth and Jacob French’s (8 great grandfather) house both served in this capacity. During the war, Daniel Gookin, Jonathan and Thomas Danforth were protective of their neighbors, the Praying Indians, resulting in threats on their lives for interceding….

Following

the war, some Indian children where placed into servitude in the homes

of local residents where they “were to be provided religious education

and taught to read the english tounge.” According to published

accounts, “a boy of twelve, son to Papa Meck, alias Dauid, late of

Warwick or Cowesit, Rhode Island, was apportioned or bound out to

Jonathan Danforth.” The boy, later known as John Warrick died on January

15, 1686 at Billerica.

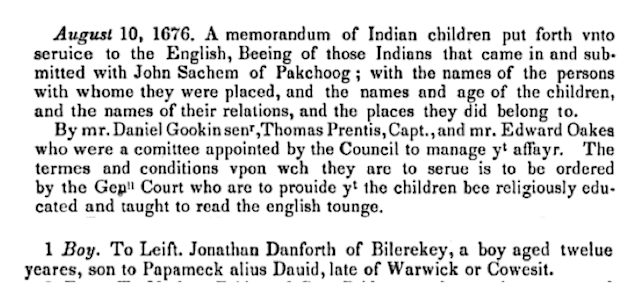

The following extract from the New England Historical and Genealogical Register, 1854 (Indian Children Put to Service) provides a listing of the children, the names and status of their parents and to whom they were been placed.

Part III – Thomas Danforth – Judge not lest ye be judged

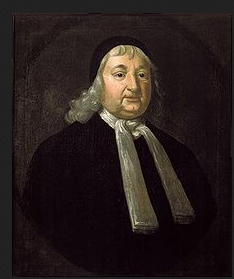

Jonathan’s brother Thomas Danforth (portrait) was the first treasurer for Harvard College and elected president of the province of Maine, then independent of the colony of Massachusetts. One published account observed, “Perhaps the most intriguing characteristic of Thomas Danforth was his willingness to stand up for his convictions despite opposition.” Considered a progressive advocate for colonists’ rights, he also was persecuted for his decent treatment of the Praying Indians during King Philip’s War.

Deputy

Governor Thomas Danforth traveled to Salem in the early months of 1692

as part of a preliminary inquiry into the matter of witchcraft being

practiced. He was not appointed to serve as one of nine judges name to

the Court of Oyer and Terminer (hear and determine) established for the Salem witch trials

and was vocal in his distaste for the manner the witchcraft proceedings

were conducted. As a demonstration of his sympathy for those swept up

in the hysteria, he provided sanctuary on his own property (Danforth

Plantation) for Salem families seeking asylum, including Sarah Cloyes

and her husband and children. (Check out this great post – Witch Caves & Salem End Road)

Additional Sources:

The Danforth Family in America – Fifth Meeting; published Boston 1886

© David R. French and French in Name Only, 2019. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited.